I had the most amazing time with my painting students on Thursday, when we went on

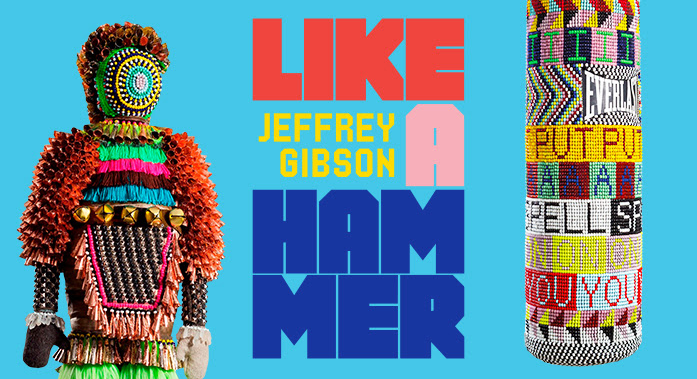

Comprised of sculptures, installation, film, paintings, and mixed media objects, Gibson’s restless aesthetics reach out across gender, sexualities, and racial lines to open our eyes and our hearts to our shared humanity, and the deep wounds felt by indigenous peoples and queer communities.

Power, politics, and all kinds of hierarchies were called into question relentlessly, but without a strident voice. Gibson’s work seduces first and foremost with his color, textures, craftsmanship; gently guiding us to a reframed state of mind. I am often wowed by creative genius and this show certainly grabbed me by the eyeballs and shook me. But more than that. He reached deep into my soul.

Stonington has been a fount of knowledge about contemporary indigenous artists from the Pacific Coast and Alaska since it opened back in the late 70s. The gallery was the very first to ever give a Native American artist a solo show in Seattle and openly acknowledges on its website that the gallery and larger city of Seattle

So imagine my heartbreak if not outright horror to pull out a piece from the stacks in the

A student asked, are they just being influenced? Another responded that it was appropriation, an I was inclined to agree. No self-reflecting artist would ever send such an outright cultural trespass out to a gallery, much less one devoted to Northwest Coast art!

I felt a little cornered by this gross example of entitlement because in the very first lecture for the class I showed slide after slide of how printmaking as a communication and art form has bridged cultural and national lines. Like language itself, it is universally human. I told these emerging talents that culture and art form part of our shared history. And here was a predatory printmaking piece that argued loudly for cultural isolationism! Philosophically, cultural isolationism is a kind of protectionism that stems from fear of the Other. Granted, people of color and indigenous peoples have a historical basis to fear the aggressions of white and European oppressors. But it’s a two-edged sword. All we have to do is look at the atrocities committed in the name of protectionism in the past (and in the present) to know that while self-defense is important, putting up walls is always a self-defeating proposition in the long run. But I didn’t say this.

The only thing I could think to say was that context matters.

I return again to the amazing Jeffrey Gibson, who is indigenous and queer and must have experienced both micro and macro aggressions, many of these cultural, but whose generous spirit broadens our cultural touchstones and his own by including other cultures and references into his work.

I’m thinking especially of his piece

That difference means that Gibson doesn’t trespass. He doesn’t appropriate. He doesn’t feel entitled to Hillel’s culture. But he is inspired by that ancient leader’s question, “If I am not for myself, then who will be for me?”

We all left the gallery in a somber mood. It was a little traumatic, actually, to discover Stonington could be selling something like that. It felt like a betrayal, though of course, they can conduct business as they like.

Thankfully, we got the chance to hear from Greg Kucera at the end of our gallery walk. His recollections of the great master, Jacob Lawrence, were