I was born in La Habana at the height of the Cold War– born into the locus of national and familial tensions. My brown father came from a Cuban socialist family, my white mother from a Spanish fascist background. It was not a union blessed by either side of the family or the Cuban state. When I was six, my entire family was punished by the Castro government and we were placed in a camp for political dissidents. For two years I was called a gusano–a worm- I was an outsider because I was part Spaniard. We were repatriated by Spain, but couldn’t stay. My father was brown and we were mixed.  The International Rescue Committee (IRC) paid for our passage to the USA, where we joined countless other refugees.

In the USA we were welcomed, but also excluded. We were kicked out of a restaurant in Florida because as the proprietor yelled, “No dogs, no Cubans, no N-words allowed!”  In Georgia I was called a porch monkey. In Massachusetts told outright that I couldn’t come to a party because I wasn’t white. Now, I am accused  by my own tribe of PoC colleagues of being white because my skin just isn’t dark enough.

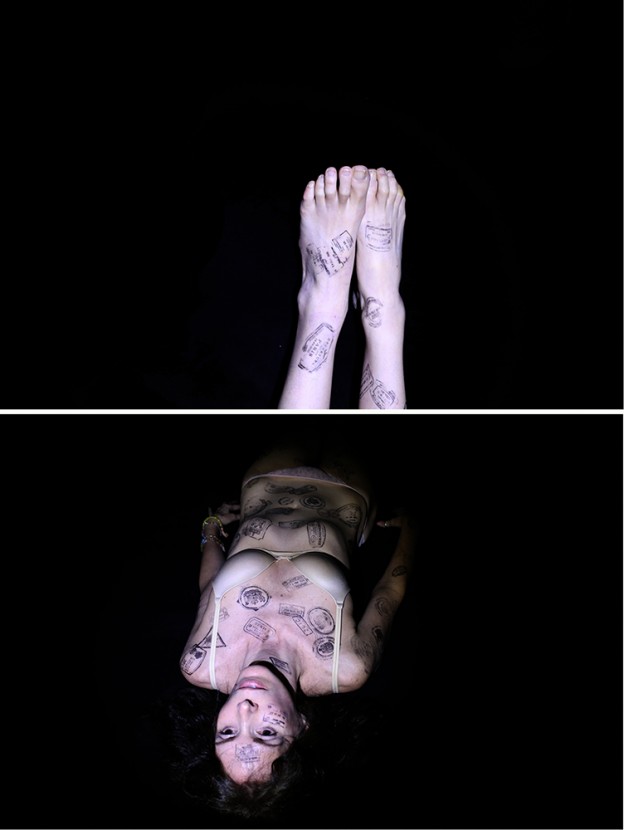

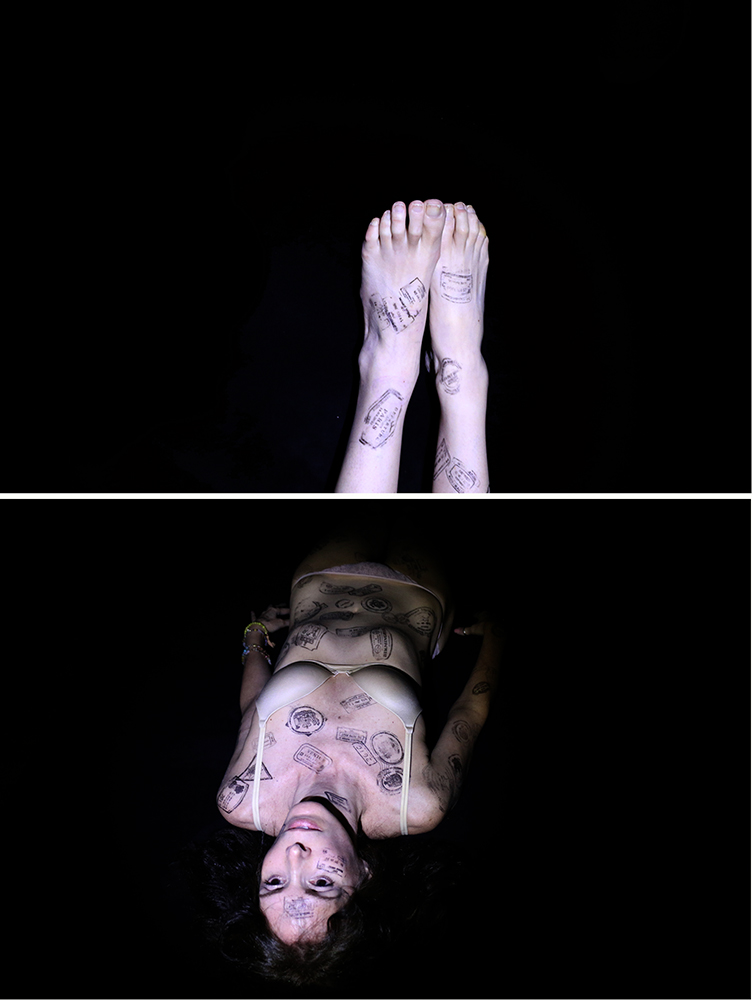

These photographic self portraits arise from the Migrations series in which I looked at the archetype of the Hanged Man as a metaphor for the suspension between places and identities experienced by outsiders.  Outsiders like me, who have to navigate the landmines of race and culture without markers to map the common territories of natal land, tongue, or ethnic identity.

This diptych takes the form of the archetypal Hanged Man, itself drawn from pittura infamante, a genre of defamatory painting displayed in public centers as a form of shaming and punishment for traitors. The dislocation of the self through corporeal and social punishment is especially resonant, given my family history and early childhood experiences.

A parallel between the body and the landscape is drawn as a spotlight reveals the many international visas stamped on my skin. We are so eager to map our borderlines between races, cultures, nations.  A searchlight blinds me in the night revealing international visas stamped on my skin.

Mirror imagery is symbolic of reflection and duality that contends with my two cultures, languages, and races. I also address the need to camouflage my vulnerability as a female outsider in a white dominated world by using a handprint as a screen.

Exodus uses photography to explore dislocation of the self as a woman of color in a white world. A map of my husband’s handprints creates a kind of maze or screen over my body, protecting me from the viewer’s gaze.